«The typography is our most beautiful ornament»: the birth of the Franciscan Printing Press

by Arianna Leonetti

Time ago, I read a book. It was written by a well-known Italian journalist, Tiziano Terzani. It is a collection of articles written right after the 9/11 drama. Some of his words draw my attention:

We need a Saint Francis again. His time was a time of crusades, like ours, but his interest was for “the others”, for those against whom the crusaders fought. He went out of his way to visit them. He tried to meet them once, but he was shipwrecked. So he tried a second time, but he got sick. At the end, during the fifth crusade, during the siege of Damietta, embittered by the behaviour of the crusaders, […] St. Francis crossed the battlefield. He was caught, enchained and drag to the Sultan. […] They may have chatted all night long, and in the morning the Sultan released him. They may have explained their reason to one another: St. Francis talked about Jesus Christ, the Sultan read from the Koran. They may have agreed on the message the Poor man from Assisi repeated everywhere: «Love your neighbour as yourself».[1]

During the delirium of the Crusades, St. Francis had the courage to be an example of peace and positivity. During a crisis – during a war! – he was so brave to cross a battlefield to teach the crusaders how to behave, how to be constructive instead of destructive, how to start a dialogue with the enemy, with the other. That is the spirit with which the Custody of the Holy Land was built, eight centuries ago.

The Custody of the Holy Land

Eight centuries ago, the Franciscan Provincia d’Oltremare (or Provincia di Terra Santa) was founded, and since the very first days of its foundation it has been called “Custody of the Holy Land”: the Franciscans who lived there had (and they still have) the hard task to safeguard and protect the Holy Land, the birthplace of the whole of Christianity. But they do not just have to look after the places where Jesus Christ was born, lived, died and resurrected. They also were responsible for the lives of the middle-eastern Christians. They always dedicated themselves to the catechetical and scholastic (but also practical) education of the Arab-speaking communities. That is why the Franciscans were pioneers in the educational field in all Palestine (the first school was founded already in the fifteenth Century). To facilitate their pedagogical mission, they always had the desire to open their own printing press.

1847: the beginning of a new era

The desire to open a Franciscan printing house in the Holy Land was destined, however, to remain frustrated for a long time. Lack of freedom and lack of economic resources were the reasons behind that huge failure. In ten years, though, this situation came to a solution through two events, both lucky and fortuitous:

- November 3rd, 1839: after the short Napoleonic occupation of the Syrian and Palestinian territories, «Catholics in Istanbul enjoyed even greater freedom and influence once the Tanzimat, the Turkish reform movement, had begun during the Sultanate of Abdulmecid».[2] This was the first step towards a completely new legislation which guaranteed equal rights to all subjects, regardless of race and religion.

- May 30th, 1844: the lack of funds was solved by the restoration of the Vienna General Commissioner. A Commissioner is an international organization (nowadays there are forty-four of its kind) that aims to raise funds for the needs of the Holy Land. «As soon as it was founded, 1) the Commissioner of Wien had the task of writing down the necessary information on the most urgent needs of the convents and worshipers [of the Holy Land]».[3]

The two major problems for which the Franciscans could not yet open their own typography seemed to have been solved.

In fact, on April 16th of 1845, Professor Giovanni Mossettizh – an expert in oriental languages – sailed to Syria with the purpose of visiting all the convents of the Middle East, collecting all the requests the friars made. The Franciscans of Saint Savior’s Monastery in Jerusalem mentioned the need to print and bind: a press, some paper and types… and someone who knew how to start a printing press and how to print in Arabic. On July 14th, 1846, Friar Sebastian Froetschner – who had been educated in the previous months in the art of printing – arrived in Jerusalem.

The main problem was to quickly train composers and printers to set the press in motion. That is why I took an adult man and three 13 and 15 years-old boys, all of them from Jerusalem, […] pupils from our school.[4]

On January 27th 1847, the first printed sheets came out from the Franciscan Printing Press: a spelling book in Arabic. It was the very first time a book was printed in Arabic throughout Palestine. This record was made even more evaluable by the fact that it was an educational tool used by the numerous catholic schools of the Middle East. The friars dream to open their own typography was completely fulfilled: they were now able to print what they need for their students.

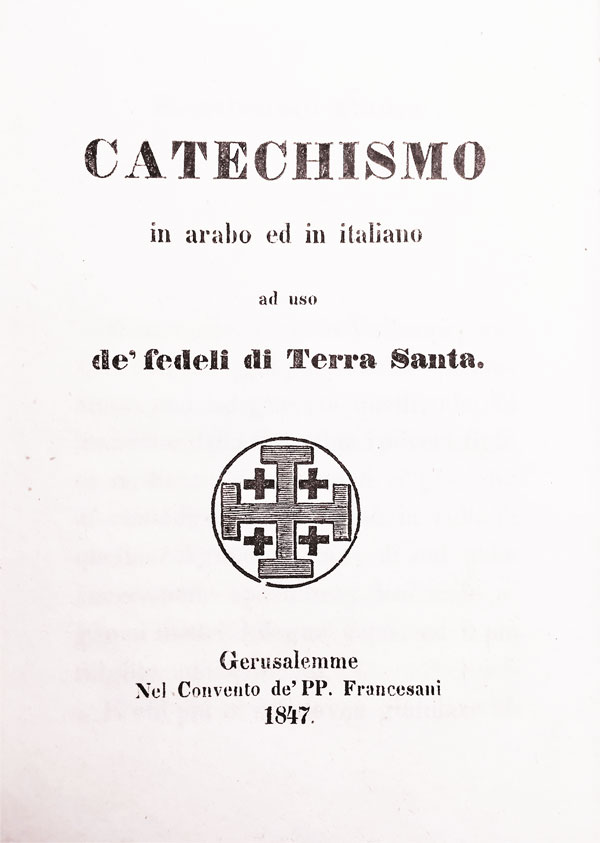

Other small works – just one or two sheets of paper, all in Arabic – were printed after the spelling book. The first real book was printed on August 1847. The Catechism of Saint Roberto Bellarmino. Spelling books, catechisms, tables for calculation… every little thing that came out from the Franciscan press was thought for their schools and students: the interest of the Franciscans was totally pedagogical.

Moreover, with the Tanzimat, even the number of schools had increased. And together with the schools, requests to the printing house also increased. The liberalism of the Turkish regime guaranteed the friars the freedom to open new schools in the Holy Land, to which students of all religions and confessions could enroll. In 32 years, the number of the schools and students almost doubled: from 29 schools with 1,631 students in 1861 to 545 schools and 3,527 students in 1893. As the Father Custos wrote in 1850, the printing house was fundamental for the achievement of their pedagogical mission: «thanks to the printing press, we compensate for all our needs and quickly propagate the principles of the true and honest. […] the typography is our most beautiful ornament; every stranger wants to visit it».[5]

So, they wanted to print themselves what was necessary for their schools and what was necessary for the majority of the population, an Arabic-speaking population. That is why it was fundamental to print in Arabic, even if it meant that they had to overcome a huge difficulty: reproducing a cursive and calligraphic script on metal. That is also why they were the only ones to print in Arabic in all Palestine. They were alone. Different from the other printing presses in Jerusalem, they were also the only ones that used local labor – with excellent results. They wanted to teach the locals how to print, how to bind, how to make types, because the educational project did not stop at the theoretical field. The Franciscan Printing Press struggled to print in Arabic using local workers – as stated in the Company guidelines – and they also provided free books to all the poor children of Egypt and Middle East. The Franciscan Printing Press was more than a simple typography or a publishing house. It was a mission. A real charitable and formative mission. And this important mission was not limited to the production of manuals in Arabic, but it went further, it was addressed to boys and men with a job to learn (and a profitable one). It was a complete human educational process. They wanted the individual to be part of the community, improving the quality of life. The typography was therefore the perfect mean to penetrate the social life of Palestine in the mid-nineteenth century.

The overcoming of great difficulties, the lack of profits, the tenacity of surviving complicated political turmoil and wars, in an even more complicated land, demonstrate the authenticity and the authentic sense of the Franciscan Printing Press.

[1] Tiziano Terzani, Lettere contro la guerra, Milano, Tea, 2016, pp. 48-9.

[2] Charles A. Frazee, Catholics & sultans. The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

[3] Notizie della missione in Terra Santa, Fascicolo I.1846, Vienna, Dai torchi della Congregazione dei PP. Mechitaristi, pp. 29-30.

[4] Froetschner’s report of 12/12/1847, from Notizie della missione in Terra Santa, Fascicolo III. 1849, pp. 22-3.

[5] Elementi di lingua araba, compilati dal P. Alessio da Livorno M: O: Mis: Ap: per uso dei collegi di Terra Santa, Gerusalemme, Tipografia dei PP: Minori Francescani, 1850, p. 3.